As I forced my way through the thicket at the base of a massive overhanging sandstone wash, a cattail from last season leapt forward, smacking me in the face. It exploded into billions of cottony seed pods, sticking in my beard, mouth, and eyes. With my eyes squeezed shut and spitting cotton, I pushed my way through only to find another dead end.

I don’t understand the desert. Its rhythms and terrain are so different from the mountains I love. Topographical maps lie, trails are impossible, and cairns were likely placed by someone else who was lost.

So I wander where I can, my mind and body going where the terrain will let me.

There is something hauntingly melancholic about the desert. It’s like the memories of experiences I never had well up inside me, forming feelings that I don’t understand — visceral emotions that can’t be articulated in words. My mind struggles to make sense of it all by cataloging my past, searching for the source of my feelings.

Distant memories?

My mind was taken back to my fourth grade Friday afternoon film strips. When I was lucky, I got to be the one to turn the knob to the sound of the little chime. Some kids turned the knob backward, but I was too afraid of getting in trouble.

The best ones were about the Colorado Anasazi (now the Ancestral Puebloans). The comforting monotone of the narrator lulled me to sleep on a warm afternoon, dust motes swimming through the projected light streaming through the gap made from where we had scooted our desks aside.

With my head resting on my folded arms, I dreamt of chipping flint points and making atlatls for hunting elk. I ate strips of dried meat while gazing out at the snow-capped Henry Mountains towering over red slickrock canyons with a light breeze that cooled my sun-drenched skin.

But wait, those are the Henry Mountains there, and I have the taste of beef jerky in my mouth now. When you’re alone for days in the desert, it’s hard to distinguish the difference between the memory of a dream and reality.

Perception crumbles like the eroded stone washed into the Dirty Devil River, turning into quicksand ready to suck you into oblivion. It is timeless here. The world is a blank canvas on which you paint the only meaning that you can. Present or past, dream or reality, it’s all what you choose.

Just like when I was little and could do, be anything.

Oppressive isolation?

What I felt in the desert didn’t come from fourth grade. Maybe it was from a more recent experience. My last trip here was filled with ghosts of past relationships. Each day, I saw groups together, enjoying each other’s company. They excitedly talked about the hoodoos they saw, the slot they’d navigated, or where they were going to eat that night. The more I was around people, the more lonely I became.

The isolation I felt came from a lack of connection. I felt empty and lost, like I was drifting with no mooring. Desert camping had associations of family and friends gathered together to enjoy the domesticity of home while being outdoors. I thought of everyone sitting around the campfire, reminiscing. Time with loved ones.

But I’ve since learned to turn feelings of isolation, where I am lacking in human connection, into blissful solitude, rich in my inner experience. This year, the emptiness was filling me up.

Maybe death?

Maybe I was thinking too metaphorically. Maybe the desert just reminds me of death. After all, the desert, like other extreme environments, is where climate change is most clearly seen. Maybe my emotions come from seeing the Earth in entropy.

The eons weigh heavily here. The ancient rock is rotting and collapsing, soughing off like the dry skin of a cadaver. Don’t trust that solid-looking rock to stand on. It may crumble underneath you. That handhold is just as likely to deteriorate into dust as hold your weight. Everything teeters on the brink. Prehistoric seabeds turned to stone, turned to sand blowing in the wind, only to form waves reminiscent of the ocean that it once was.

Life clings to the edge. It’s no wonder that a Mars research station is located nearby. This is as close to a dead planet as you can find. The living things that abide here are cantankerous old men searching for a fight. Thorns, needles, spiky leaves, spearheads, hooked barbs, poison, stingers, horns, and fangs scream, “Leave me alone and let me die in peace.”

But not every desert denizen received the memo that it must be harsh and crabby. The bed of the Dirty Devil River was soft and inviting. The cool, wet sand sensuously caressed my hot and tired feet as I waded along its meandering form like a pleasant beach walk.

Astonishingly, I came around a bend in a desolate sandstone canyon surrounded by thousands of square miles of desert, only to discover a beaver dam. Somehow, this water-loving species has maintained a desert residence. I am sure their cuisine did not include fish in this muddy water, but they did create a riparian habitat for frogs and other soft water-loving animals. Is a frog ranch enough to sustain a family of beavers?

I left my tracks in the sandy bottomed wash. If I stuck to the swiftest part of the stream, water only inches deep, the sand tended to be a bit coarser and firmer. When getting out of the main current, though, I became bogged down by shoe sucking mud. This viscous element quickly turned from a walkable surface to gunky liquid just by exerting a gentle wiggling pressure. I thought about a dinosaur footprint I saw etched into stone, many millions of years old.

Suddenly, my foot was buried up to the ankle and required significant force to pull it slurping back up. My feet started getting sucked deeper with every step. Panicked, I lunged towards the muddy shoreline only to find what appeared to be dry was sucking at me, too. It was as if the Earth didn’t want to wait for me to die a natural death. Instead, it tried to pull me into a dinosaur grave.

The creek, which I wandered up today, may have been muddy and fairly nasty, but it had one thing going for it — no trash. I saw no styrofoam wrappers, McDonald’s Happy meal bags, 7-Eleven big cups, discarded tires, nor even the iridescent sheen of the petroleum products that we love so much. The resourceful beaver hadn’t collected any 2x4s or old fence posts to leave protruding from its dam. This muddy creek was dirty in the healthiest of ways: it was filled with dirt. But since when does dirt hurt?

If the desert is where the Earth is dying first, then it is dying with dignity, on its own terms, without the humiliation of being scarred with the detritus of humanity. At least it’s a beautiful death.

There’s no translation

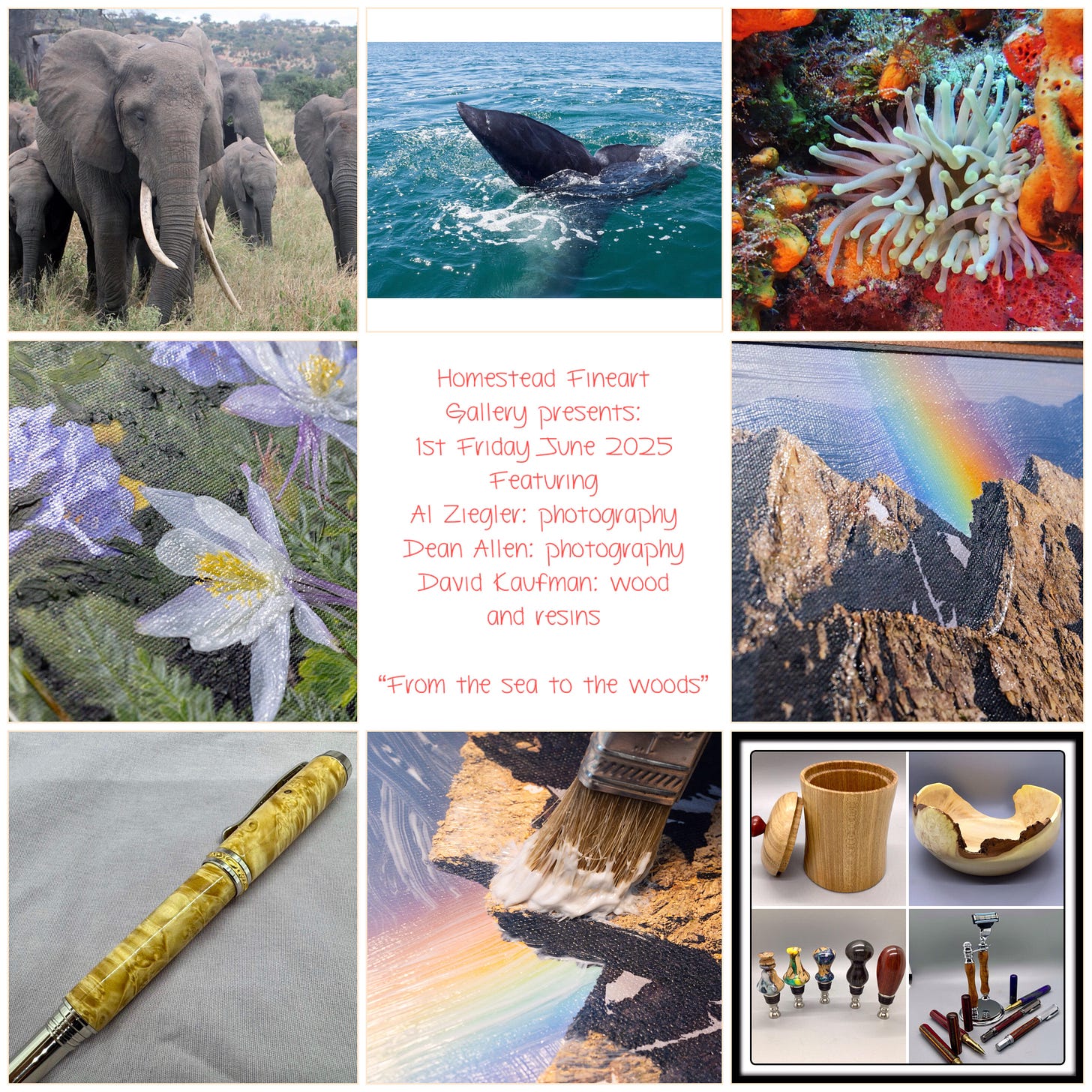

My myriad ruminations might be interesting, but they still fall short of describing what I felt. Luckily, I had my camera with me. Perhaps the images I took express my feelings better than any word or story can.

It may be counterproductive to try describing a photograph in words. How can you use verbal language to explain an emotion expressed visually? It’s like writing a chord progression to describe how a song makes you feel. Or cataloging the number of nouns, adjectives, and verbs to explain a poem’s meaning.

It’s inaccurate to believe that there is a direct translation from a visual language into a verbal one. That is why we have the arts; paintings, sculpture, photography, music, poetry, and dance all have their own language that cannot be expressed any other way.

I am grateful that we have cameras to take to incredible places where we can explore our inner landscape. My memories of childhood, the conflicting feelings of isolation and solitude, and the loss felt through the entropy of Earth are only variables in a larger equation. They simply skirt the edges of indescribable emotions. I hope my photography is able to convey those emotions, which I can’t seem to express any other way.

Words have their limits, but light doesn’t. The images in my gallery, Desert Mindscapes, continue where this essay leaves off. They speak in sand, shadow, and silence — no translation necessary.

➝ creationimagesphotography.com/desert